Why Haskell is super cool

Published October 17, 2025

My new favorite programming language to play around in is Haskell. I like it because it is extremely mathematical in nature, and lends itself to very elegant solutions. Here, I am going to walk through an example program I made to solve a problem. But first, here are some things you need to know.

- Haskell applies functions with spaces, not with parenthesis.

For example, in most programming languages, you take the absolute value of a number by writing something like

abs(n). In Haskell, you writeabs n. - Everything in Haskell is lazily evaluated. This basically means that everything is computed at the last possible moment. When you evaluate a function, Haskell basically says “Yeah yeah, I get what you mean and I’ll actually compute it later when you ask for the result.” A huge advantage of this is that you can write infinite lists, and the computer will only calculate the ones you want.

- Everything in Haskell is typed.

For example, a function would have type

f :: a -> bwritten in Haskell, meaning it has one parameter of typeaand returns one thing of typeb. In this problem we don’t see anything more complicated than this, but the type system in Haskell is very extensible and is one of its major strengths. - Haskell is a purely functional programming language. This means that everything in it is a function that returns something, and they can’t have any side effects. Side effects are things like printing to the screen, modifying the value of a variable, reading/writing data, among others. As you can see, this list incorporates almost everything useful that a computer program can do. In order to do these things in Haskell, you need to wrap them monads, some of which are incorporated into the language by default. The benefit of this is that it confines all the side effects to a specific spot, which allows you to reason about the rest of your code as pure mathematical functions.

- There are no if/else or loop statements.

This is a consequence of being purely functional.

forloops require a variable to be modified in place, which isn’t possible in Haskell. There is a version of if/else, but it doesn’t work the way it does in other languages. The patternwhile Trueis also not possible, because exiting the infinite loop would require some kind ofbreakstatement, which is a side effect. Instead of all of these control flow statements, Haskell encourages recursive definitions, which compliments the lazy-loading property.

Ok, so the problem I’m solving comes from Project Euler. This is a essentially a huge repository of math problems, and the challenge is to write an algorithm that solves them. There are almost 1000 posted, and some of the later ones are extremely difficult and have only been solved by ~30 people. I’m solving #36 here, which is one of the simpler ones. The task is to find the sum of all the numbers under 1 million that are palindromic in both base 10 and base 2. For example, the number is in base 2, and both representations are the same forwards and backwards.

So to start, we need a function that can tell if something is a palindrome:

isPalindrome :: String -> Bool

isPalindrome n = n == reverse nIt’s pretty simple, it just takes one parameter as a string and checks if it is the same forwards and back and returns True or False, using the readily available reverse function. The weird capitalization is a convention in Haskell because functions can’t actually start with a capital letter. Next we need a function to convert a number from base 10 to base 2:

base2 :: Int -> String

base2 n = reverse (russianPeasant n)

where

russianPeasant :: Int -> String

russianPeasant 0 = ""

russianPeasant n = let (q, r) = n `divMod` 2 in show r ++ russianPeasant qThis function takes a number and returns a string where the string is the number in base 2. For example base2 585 returns "1001001001". It returns a string for easy input into the isPalindrome function. It’s implemented using the Russian peasant method of converting between bases. This algorithm repeatedly divides a number in half, keeping track of the remainder each time. The number in base 2 is the remainders read from last to first, hence the reverse statement in the definition. Here we can see recursion at work: the base case is russianPeasant 0 = "", so if there is nothing left the process terminates. russianPeasant n is defined recursively using divMod, a function supplied by default that returns the quotient and the remainder. Then, we concatenate the remainder with russianPeasant called on the quotient, knowing that the process will terminate once the quotient is 0 due to our base case.

Another cool feature of Haskell is that any function can be made an infix operator by surrounding it in backticks. Here, instead of writing divMod n 2 we can write the much more natural n divMod 2. Pretty cool. Next we have two functions to check if a number is a palindrome in base 10 or in base 2:

base10Pal :: Int -> Bool

base10Pal = isPalindrome . show

base2Pal :: Int -> Bool

base2Pal = isPalindrome . base2

p35 :: Int -> Bool

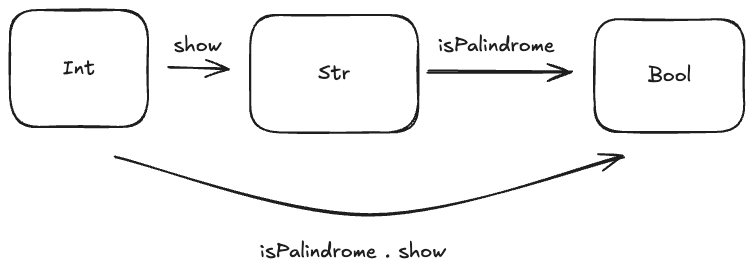

p35 n = base10Pal n && base2Pal nThey both have the same type Int -> Bool, so they take an integer and return true or false. The . represents function composition. show just turns an integer into a string for input into isPalindrome. A picture helps:  As you can see,

As you can see, isPalindrome . show takes the output of show as the input into isPalindrome. The base 2 function works similarly, except it uses base2 to convert to base 2 instead of show. p35 is a function that takes an integer and returns True if it is a palindrome in both base 10 and base 2, using the logical and between our two functions. All that’s left is to compute our solution!

limit :: Int

limit = 10 ^ 6

answer :: Int

answer = sum [x | x <- [1, 3 .. limit], p35 x]

main :: IO ()

main = print answerlimit just equals one million. answer is where all the computation lies. it uses Haskell’s list comprehension feature to find all x in the numbers up to one million such that p35 x is true, and then computes their sum. There’s one more trick, too. We don’t have to check even numbers, since even numbers in base 2 always start with 1 and end with 0, making palindromes impossible. This computation represents the following in set notation:

As you can see, the Haskell syntax is basically the same. Finally, in order to actually print the answer to the screen, we need a main function to be executed. main is of type IO (), which is one of those monad wrapper values so we can perform side effects like printing the value of answer to the screen.

So that’s it! I find this solution to be very simple and elegant, and Haskell facilitates my natural problem solving process. I’m sure in a lower level language there are many optimizations to be had. For instance, numbers are already converted to base 2 to be stored on a computer, so I’m sure there are ways to get a base 2 representation of a number near instantaneously. Also, I am aware that in my code for base2 the reverse function is redundant as I am checking for palindromes anyway, but I left it in for clarity. The full code is here:

isPalindrome :: String -> Bool

isPalindrome n = n == reverse n

base2 :: Int -> String

base2 n = reverse (russianPeasant n)

where

russianPeasant :: Int -> String

russianPeasant 0 = ""

russianPeasant n = let (q, r) = n `divMod` 2 in show r ++ russianPeasant q

base10Pal :: Int -> Bool

base10Pal = isPalindrome . show

base2Pal :: Int -> Bool

base2Pal = isPalindrome . base2

p35 :: Int -> Bool

p35 n = base10Pal n && base2Pal n

limit :: Int

limit = 10 ^ 6

answer :: Int

answer = sum [x | x <- [1, 3 .. limit], p35 x]

main :: IO ()

main = print answerIt runs in about 29 milliseconds on my M2 Macbook Pro.