Things I learned making mmath

Published December 1, 2025

A little while ago, I decided I wanted to memorize my times tables up to 20, and just generally practice my mental math skills. The impetus for this was that mental arithmetic is often the first thing that people ask me about when they learn that I studied mathematics in college, and having some more basic competency would be useful. I want to get better at addition and subtraction of three digit numbers, and multiplication of two digit numbers. People are always impressed and it can be a nice little flex.

So, I started searching for some application that would generate questions for me to answer. Surprisingly, I came up short. There are tons of apps for kids learning their times tables up to 10 or 12, but past that there’s not many options. They don’t allow for setting any arbitrary limit on where you want to practice. I found a couple apps that seemed promising but showed ads after every 5 questions or locked many features behind a subscription, which is just unacceptable to me. Notably, I couldn’t find any open source applications. I decided to make my own.

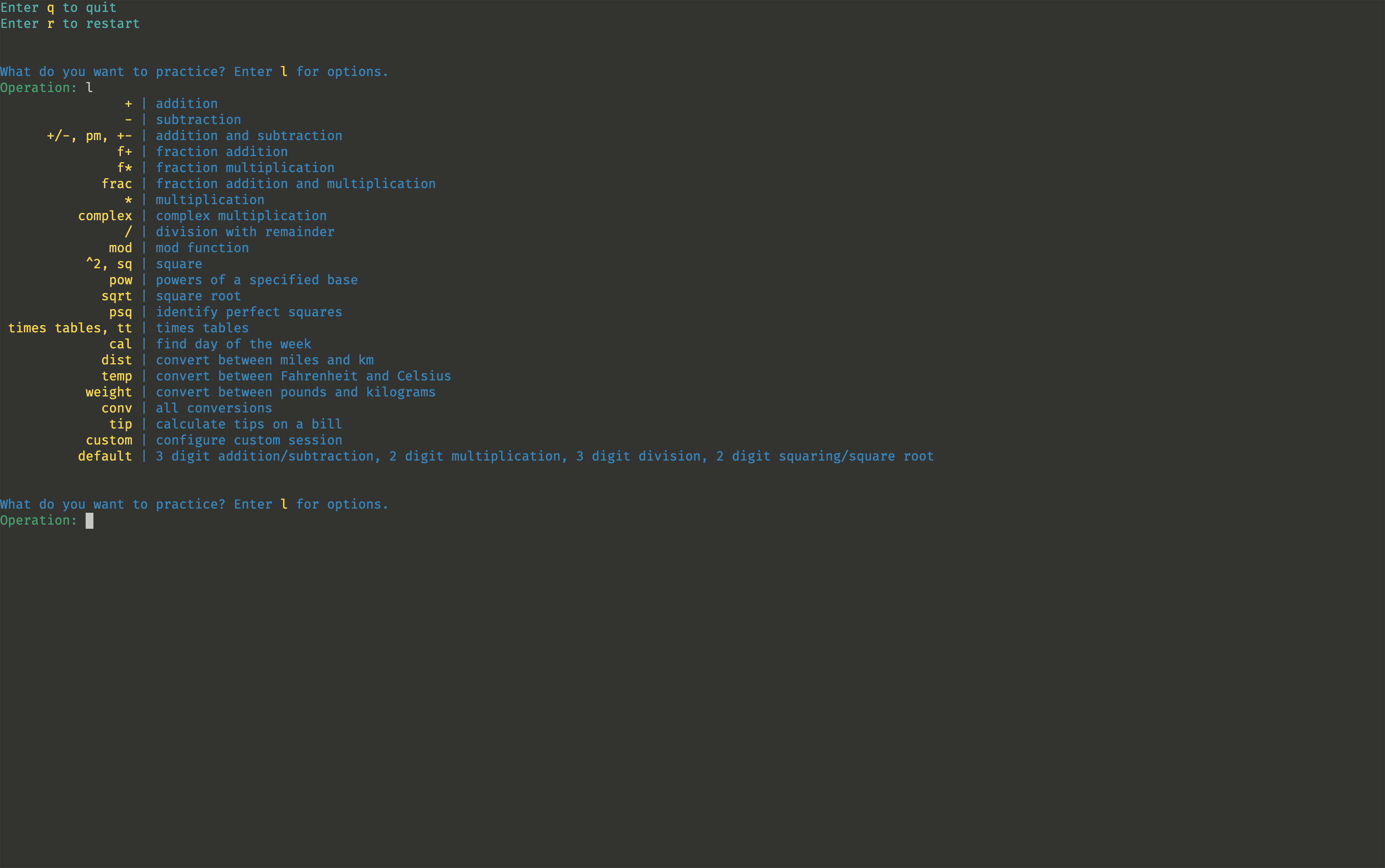

The first version

I had to choose which programming language to write it in. My options were Rust, Haskell, or Python. Rust would’ve been a great choice, but I wanted to get something working without dealing with it’s quirks. And while I love Haskell, an app with so much user input and random number generation seemed daunting to write in a purely functional language. So I chose Python because I was comfortable with it and wanted to develop quickly. Within an hour, I had a simple model that worked for me at the most basic level. It supported addition, subtraction, and multiplication.

I developed it into a full app where you can select operations and essentially configure it to your liking. You get a data screen at the end with summary statistics about your quiz. It was colored all nicely using the colorama package.

The interface worked by continuously clearing and reprinting the UI. I knew this could not be the best solution, but it was the simplest and works just fine. The biggest problem I faced was errors resulting from the user not inputting the correct value. To solve this, I crafted 3 different custom input functions, one for each type of input I wanted: text, integers, and decimals. The functions handled all the errors themselves, so I didn’t have to worry about the input anymore.

The biggest innovation I had when developing this version of the program is creating a QuestionResult dataclass.

@dataclass

class QuestionResult:

num_wrong: int

question_time: float

question_info: tuple[str, str, str] | tuple[str, str]

Once I had this, I rapidly added tons of new question types, like unit conversions and complex multiplication. All I had to do was design a function that returned a QuestionResult data type, and everything else would be handled automatically.

I also wanted the user to be able to enter q to quit the program at any time, and r to go back to the main menu. Quitting is easy, all I had to do was check if the input was q in my custom input functions and raise a SystemExit exception. The restart feature confused me for a long time. I couldn’t find a way to restart at any time without adding a bunch of checks in every different place. Then, I realized I could do it in the exact same way. I created a RestartProgram exception, raised it whenever the user input r, and caught it in my main loop. I believe using exceptions to control flow like this is a very common pattern, but I had never used it before so it didn’t come naturally.

In the end, it was a very functional program that I used to practice my mental arithmetic. Still, I wasn’t happy with the way I was clearing and printing the screen on every new question. Although it totally worked, I wanted to make a true terminal interface the way other programs such as nano had, but I had no idea how those worked. Although much more limited than a full graphical user interface, I like the aesthetic of terminal user interfaces. They are boxy and hacker-like, and from what I understand you don’t have to worry about performance as much as with GUIs.

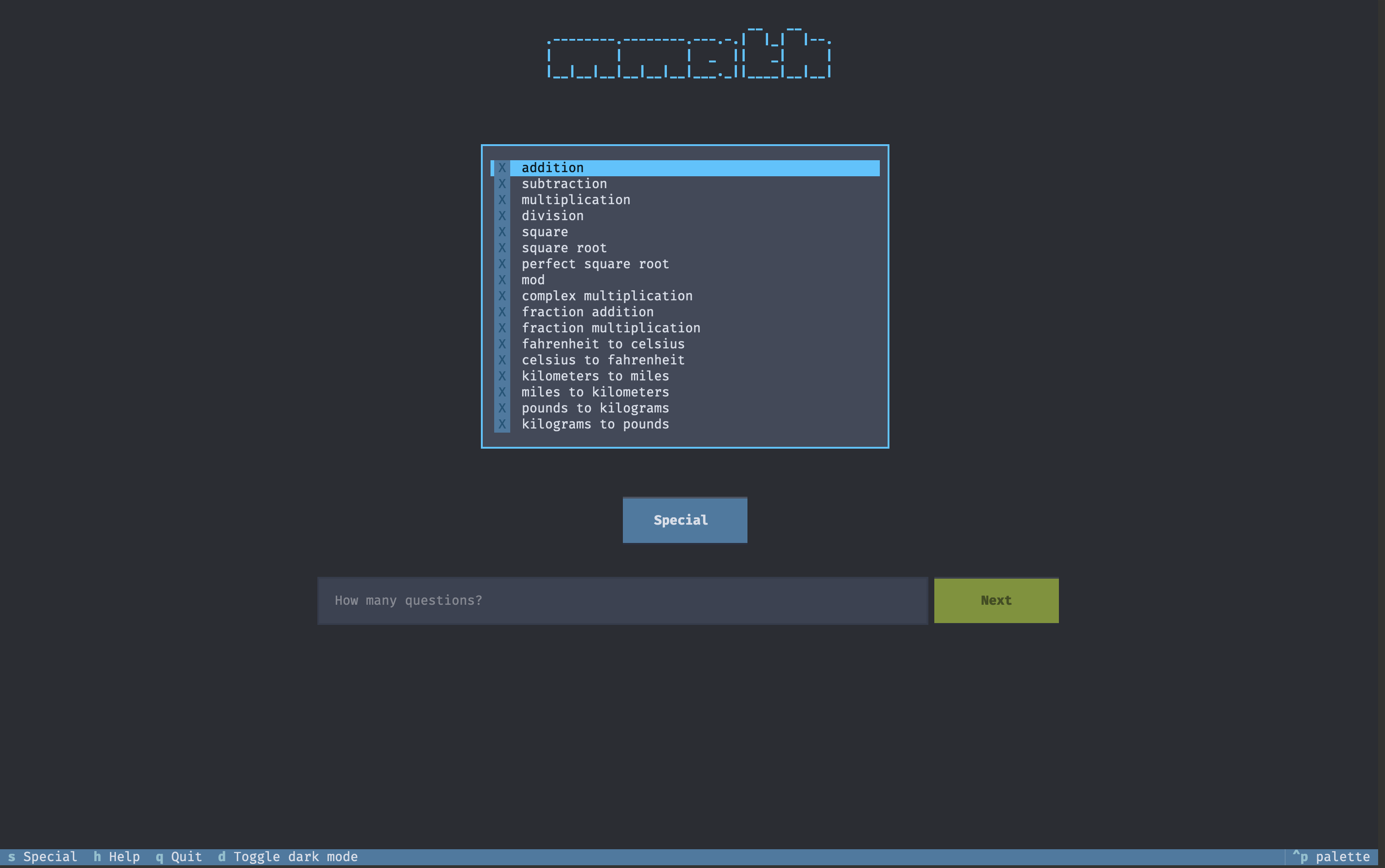

Version two

I realized pretty quickly that making a terminal interface would require an entire rewrite of the program. I would not be able to just copy most of the code. There are many TUI libraries I could use in Python, from the built-in curses module to the most advanced textual library. With curses, I could’ve probably just replaced my print calls with addstr, but then my app would look and function the exact same way, it would just print on an overlay instead of directly in the terminal. For so much effort, I wanted something that would be significantly different. Since I had to rewrite it anyway, I considered using a different language with a static type system, such as Rust, Haskell, or Go, all of which have their own popular TUI libraries. As the program grew larger, some of the limitations of Python started to show. Python’s flexibility made it easy to prototype, but following the data through the program and ensuring I wouldn’t get any type errors became a hassle. In the end though, I used Python again, choosing the textual module since I wanted to continue to practice my Python skills.

textual is a very mature open source library with tons of functionality that I barely scratched the surface of. The documentation is superb, with a super helpful tutorial and guide that was my primary resource to learn from. The library mainly uses Python classes, which is an aspect of Python I don’t frequently use. I usually compose functions to get the behavior I want. The design of textual is around Screens and Widgets. Screens work like a stack, where they get pushed and popped off the top. Screens contain Widgets, which are the things like buttons and text that you see.

Since I basically already knew all of the functionality I wanted, really the only issue was learning how to use the library. Again, I had barely used classes before this, so I had to get used to defining properties and methods, instead of function inputs and outputs.

It took four tries to finally figure out how I wanted to structure my app. I wasn’t sure of the best way to do things; textual has a ton of features and wasn’t sure which ones would be the best for what I wanted. I couldn’t decide if I wanted a new screen for each question, or just one that got updated. My final design has a main menu screen, a configuration screen, a question screen, and a final data screen.

One super cool thing I learned is about Python’s abstract base classes. Similar to my QuestionResult dataclass, I needed some common framework for my question types so they could easily be interchanged with each other. I wanted something like what Haskell classes are. In Haskell, there is a concept of a class (very different from Python classes), which defines a Haskell type to be a part of a broader category. For instance, for a type to be part of the Num class, you need to define +, -, *, /, abs, negate, signum, and FromInteger. Without going into too much detail, these are the functions that mean that the type can act as a number, so it can be added, subtracted, multiplied with other instances of the same type. Python’s type system is not nearly as robust as Haskell’s, but I learned of Python’s abstract base classes (ABCs) and Protocols, which do similar things. Abstract base classes are classes that are designed to be inherited from, and they define common functionality. Protocols are similar, but instead of being inherited from, if something implements the same methods and properties, it is a member of the protocol (a concept known as duck typing).

I used an abstract base class as follows:

class QuestionInfo(ABC):

textual_input_type: str | None = None

input_restrictions: str | None = None

def __init__(self, **kwargs: int) -> None:

self.left: float | str = ""

self.right: float | str = ""

self.symbol: str = ""

self.correct: float | complex | tuple[int, int] | None = None

self.display: str = ""

self.special: dict[str, int] | None = kwargs

@abstractmethod

def new(self, top: int) -> None:

"""Generate a new question."""

@abstractmethod

def verify_correct(self, usr_input: str) -> bool:

"""Check correctness."""Each of my question types inherits from this base class. They all define exactly two methods: one to generate a new question, and one to verify that an answer is correct. Some operations, like addition, take two inputs, and others, like taking the square root, take only one. Similarly, some operations need a specific value, and others accept answers within a certain range. In this way, each operation can define its own way of generating a new question and verifying correctness, but since they inherit from the base class, they can be guaranteed to behave similarly.

The textual library made a lot of things super easy once I figured out how to use it. Really the most difficult part was deciding how I wanted to implement certain features. Do I want the “end quiz once all the questions are answered” logic to be contained in the question number display widget, or in the broader question UI screen? I chose the latter, and the question number display widget only contains the current question number. How do I want to inform the user if they got the question right or wrong? I chose to flash green or red on the screen for 0.15 seconds.

One issue I consistently ran into was styling. texual uses a special kind of CSS to handle styling, and I was constantly running into problems with widgets not showing up, not centering the way I expect them, or just behaving in odd ways. I also had to think about how I wanted the whole app to look and how I wanted to navigate the app. Answering questions like these are where most of my time was spent.

Conclusion

I gained a new respect for Python from building this application. I was guilty of thinking of Python as kind of a beginner programming language due to it’s simplicity. I knew it was powerful for its statistics and machine learning libraries, but those aren’t even really Python. I read a lot of the official Python documentation, and I didn’t realize how vast Python’s standard library was. You can use the basic functionality, but you are also given lots of control through the use of its special methods (also known as dunder methods). There are some modules included in the standard library that give Python some very powerful features. The dynamic type system, the fact that it is interpreted rather than compiled, and overall slowness of computation are still things to consider (and are often downsides in my eyes), but it is by no means a toy language.

Now that the main application is complete, I realize why every app costs money. Making a well thought out app with all the features you need takes a special skill set and a lot of time, and people want to be compensated for it. Open source maintainers and contributors are true heroes for donating their time and expertise for free.

I am also glad I spent a long time learning other programming languages. They each encourage a different approach, but also often have the same features. I probably wouldn’t have discovered Python’s abstract base classes if I hadn’t learned some Haskell and thought “wow, I wish I had that feature right now.” I took a kind of breadth over depth approach, trying to dip my toes into whatever seemed interesting, and I don’t regret it.

I still want to add some kind of data storage that persists between sessions, and a place to test your memory of digits of and , but for the moment I’m going to focus on something else. I’m going to use it to actually learn the times tables I originally set out to do, get back to studying mathematics and computer science.